I’m a firm believer in the whole mind like water spiel that David Allen preaches through GTD. I jumped on the Gettings Things Done bandwagon around 2004 I think – the first of my two senior years in college. And here we are in 2020, which means I’ve been practicing this methodology (with varying levels of success) for over fifteen years. And now, looking back, I can see that it was probably 2010 – six years in! – before I became truly comfortable with letting go; before that whole mind like water state of flow finally became second nature.

For me, and I guess most people doing the GTD thing, getting to that point meant fully trusting your system. And that’s exactly what I mean when I say “letting go” above. You have to train yourself to be diligent enough that putting everything into your system becomes habit. And you have to trust your system (paper, digital, whatever) enough so that all those open loops in your head fall away and you can just let go and go about your life confidently.

Years ago, I worked on a piece of medical software that was designed to ensure surgeons operated on the correct side and limb of the patient’s body. It’s the 21st century; you’d think the medical industry would have fixed that problem by now, right? But even after verbally confirming with the patient before surgery, and then even after marking the incision site with a Sharpie, doctors still occasionally operate on the wrong part of the body. The software I helped build aimed to solve this problem by being a glorified, cloud-synced checklist that hospitals could buy for tens of thousands of dollars per license. (Enterprise software sales is ridiculous.) And I’ll be damned, but the research showed that medical facilities using our software reported a statistical decrease in operating room screwups.

That point of that story is to say that checklists – particularly ones that recur and involve multiple, detailed steps – can be an amazing tool to have at your disposal. And learning to use them was a huge part in my own journey towards letting go of all the crap in my head.

And so, for a long time now, I’ve been using checklists for all of the recurring, multi-step projects in my life. Here are some examples:

- Releasing an update to one of my Mac apps is a twelve step process. Some of it can be automated – but not all. And if I forget or mess up any one of those steps, it could botch the whole release.

- At the start of every month, I sort, organize, and backup all of the photos and videos my family took during the previous month. Because of the sheer quantity of data we generate every 30 days – and also the fact that I’m slightly crazy and don’t trust any single cloud provider with my memories – that backup process involves syncing tens of gigabytes of data and a bunch of shell commands. Once again, it’s not something I trust myself to get right every time on my own.

- Every three months I have to renew and ship an updated SSL certificate inside one of my apps. If I forget, or if I mess up, my customers won’t be able to get their work done. This is also another fairly involved process that I can’t easily automate, so I have to do it by hand.

Originally, and for nearly a decade, all of those checklists lived inside OmniFocus as recurring projects. And by and large that worked really, really well. But in early 2019, when I found myself with a bunch of free time on my hands, I took a week to reevaluate all of the systems, inboxes, apps, and habits I use to get life done. One of the best changes that came out of that week was a new approach to handling those repeating projects. And it makes use of two of my very-most-favorite apps: TaskPaper and Keyboard Maestro.

They key insight I had was that while my checklists in OmniFocus were definitely helping make sure I do the things I’m supposed to do, they were limiting in two ways:

- Tasks in OmniFocus aren’t very good at holding detailed information about the task – information you might need to actually do the task. There are a few standard approaches to solving this limitation. OmniFocus does have a “Notes” field associated with each task, but it’s basically just a small textview – not really anything you would want to type in or view a sizable amount of text with. Or, you could use the “Notes” field as a pointer to link to some other actual document in your reference system. Many apps now let you copy a unique URL that will link back to the source document. That’s super handy, but in practice I’ve always found it a bit clunky, clumsy, and fragile.

- The other drawback to having everything in OmniFocus was that I was not capturing any of the metadata around those tasks as I completed them. When you mark a task complete in OmniFocus, the only thing that’s actually recorded is the completion date. If something unusual happens or goes wrong with one of my tasks, I don’t really have a way for my future self to reference or learn from the mistake. Or say everything went totally fine and normal, but I just need to store some piece of information particular to a task. Where does that go? Again, OmniFocus has that “Notes” field, but I just don’t find it very usable in practice – especially since the app isn’t really optimized for going back in time to reference past actions. (Nor should it be, really.)

To fix those two shortcomings, what I ended up doing was converting all of those recurring projects into TaskPaper documents. Each document contains all of the actions for the project, which of course can be nested and organized just like they were structured in OmniFocus. Then, back in OmniFocus, I deleted the project and replaced it with a single recurring task that reminds me when it’s time to start the project again.

When that time arrives, I make a duplicate of the template TaskPaper document just for that specific recurrence of the project and work my way through the checklist like normal. Having everything stored inside the TaskPaper document solves the two problems above.

- It’s a plain text file that can be opened with TaskPaper or any other text editor. So, I’m free to add in as much supporting material for each task as I want. I can literally drop in paragraphs and paragraphs of prose between each task if I need to. Or, some of those projects might require technical details. I can just inline those in the document itself. The same goes for actual URLs linking to other supporting materials or websites.

- If I need to take notes, remember anything about a particular task as it happens, or record the outcome or any results of the work, I store that in the document, too. That way, everything is self-contained and in the correct context if I ever need to reference what happened. And, again, since it’s all plain text – everything is easily searchable from Spotlight all the way down to

grep.

After the project is complete, I file away the TaskPaper document for safe keeping.

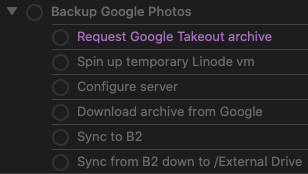

So that’s the theory behind the system I’ve migrated to – and it works great. But what does it actually look like in practice? As an example, let’s look at my monthly project that backs up my family’s photos and videos. (My workflow is slightly insane, but I have “reasons”.) In OmniFocus, that project looked like this:

And that’s great. That gets the job done and makes sure I don’t miss a step. It also helps because some of these steps can take an hour or more of waiting around for data to transfer, so if I get distracted by something else while waiting, I know exactly where to pick back up from.

But, there’s also a lot of complexity behind each of those actions. The “configure server” step involves running a shell script. Where should that be stored? I find it’s a bit of a balancing act between keeping reference material contextualized alongside the task itself vs keeping it in some type of external storage (DEVONthink, Evernote, Apple Notes, Bear, etc). In this particular case, I like having it right there. And that’s not very easy with OmniFocus. (This isn’t me bitching about OF. I don’t think or know if it should even be a use case they support. There are better tools for that job, which is what I’m leading up to.)

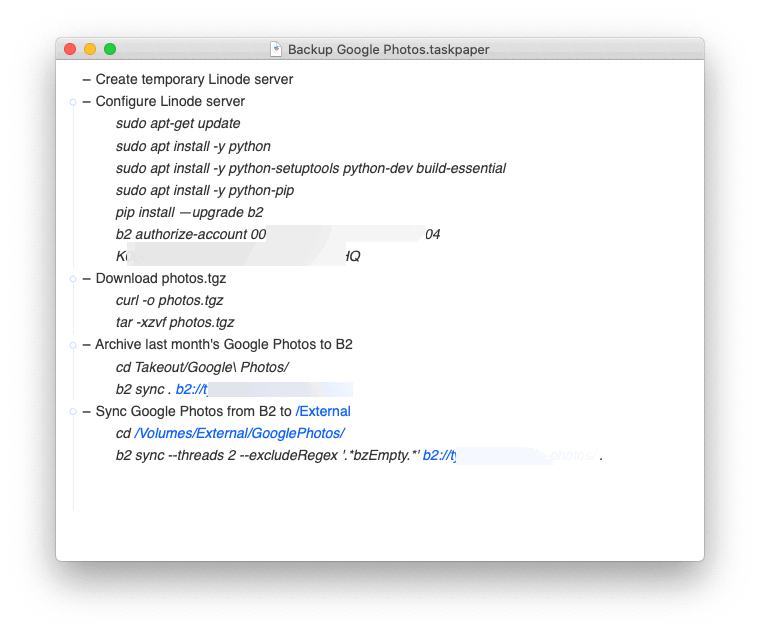

Now, compare that to what the TaskPaper document for that project looks like:

Same thing – but now I can inline the information I need to complete each step. For this project, that happens to be all of the necessary shell commands.

So, ?, TaskPaper is great for this sort of thing. But as more and more of those documents are created each week and month, where do they all go? How are they managed, etc? Glad you asked.

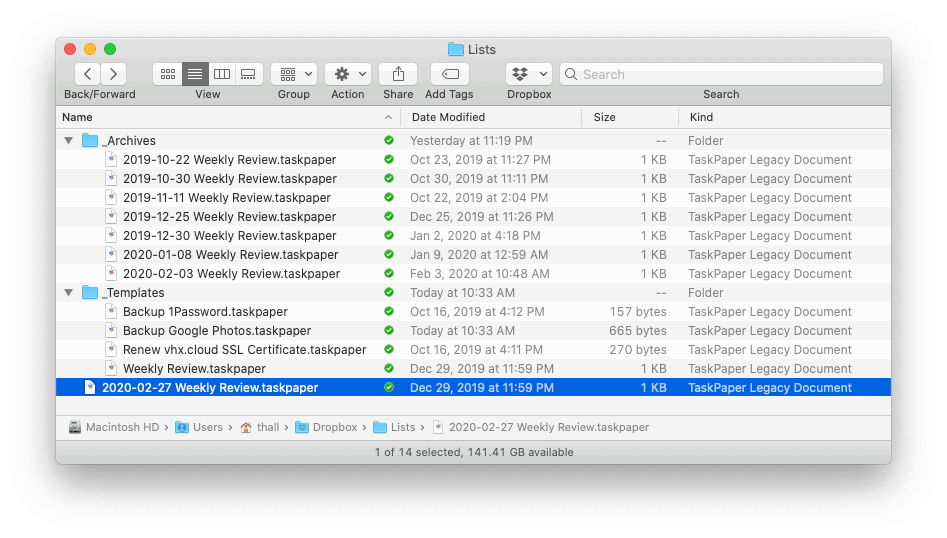

They’re stored in a simple directory structure in a dedicated Dropbox folder, so they’re in sync and available on every device.

(I’ve removed a year’s worth of archives from that screenshot so you can see the full folder structure in a single image.)

It works like this:

Listsis a top-level folder in my~/Dropbox. The checklists that are active / incomplete and that I’m currently working on live in this folder._Templatesstores the templates / original copies of the TaskPaper documents that I duplicate and work from._Archivesis where the files go once they’re completed so I have a single place to search / reference in the future. Also, many times, it’s where incomplete lists go once I give up and abandon one for whatever reason – as is often the case when I just don’t get around to completely finishing my weekly review every Sunday.

Each file has the same name as the template it was duplicated from but with the current date prepended so I can keep track of things and also sort by date in Finder.

I know all of this may sound like overkill to lots of people (especially to my family and coworkers as I watch their eyes glaze over when I get excited and start rambling on about this stuff), but it keeps me on track. More importantly, because I have this system in place – one that works for my weird, specific way of doing things – it truly allows me to let go and do my work knowing that things won’t fall through the cracks.

When I first read the GTD book and was introduced to mind like water and all that stuff, the idea was fascinating to me because it echoed the feeling of flow that most developers (and tons of other creatives and professions, of course) strive to get into when doing focused work. And not having a bunch of baggage in your head about all the things you need to do but can’t yet actually do is freeing and makes it easier for me to do my best work.

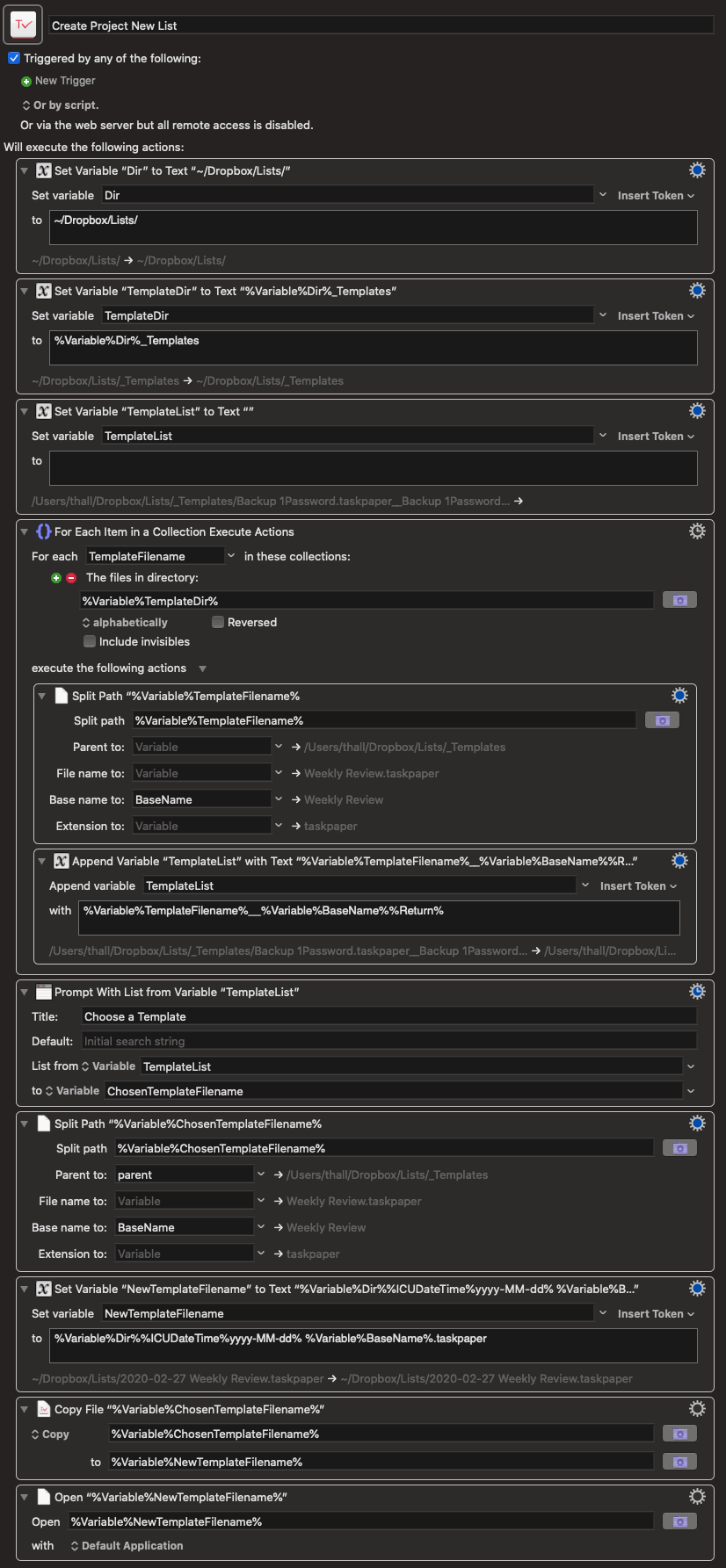

Ok, enough philosophizing. Here’s the last thing. It’s a quick Keyboard Maestro macro I wrote that makes this workflow instant.

At any time on my Mac, I can hit ⌘⇧\ (my keyboard shortcut to bring up KM’s macro picker), type the name of a list template, and press ↵. Keyboard Maestro will duplicate the template, put it in the correct folder, give it the appropriate date formatted filename, and open it in TaskPaper.

The macro is smart in that you don’t have to manually specify each list you want to work with. Instead, just add a new template into the _Templates folder, and Keyboard Maestro will read its directory contents each time you run the macro. That way, everything’s always current and available.

And here’s the macro in all its glory, which you can download.