It all started Tuesday afternoon when a reader commented on an old blog post that they were using NFC stickers to launch Shortcuts on their iPhone.

I can’t explain how or why my brain jumps around the way it does, but it immediately connected that idea with Brett Terpstra’s fantastic Bunch.app. I’ve been using his app for months now to automate opening, well, a bunch of apps at once. Like when I arrive at work or do other context switches.

Right now, I trigger those bunches with a keyboard shortcut, but for no other reason than “it might be cool if…”, I wondered if I could do the same thing with an NFC tap.

More broadly speaking: I wondered if I could automate actions on my Mac from my phone?

I won’t leave you in suspense. Here’s the result, which I’ll explain below.

You’ll see I tap my phone on an NFC sticker on my desk at work, and all of my work applications launch on my Mac.

To make this work, I needed to find a way to trigger my Mac from an iOS Shortcut.

I’ve written previously about one method that uses Hazel on macOS to react to a new file appearing in a synced iCloud Drive folder and run commands.

I got that solution working in this situation, but iCloud Drive is often nowhere near real-time enough like Dropbox. (And the Shortcuts.app requirement means I need to use iCloud Drive.) So, while it technically worked, it was slow and unpredictable. The latency between NFC tap and my Mac reacting would vary from 3 seconds to 10 seconds to never until I opened Files.app on my phone.

So, I needed a faster solution. A way to send a command directly from my phone (or maybe any other device?) to my Mac.

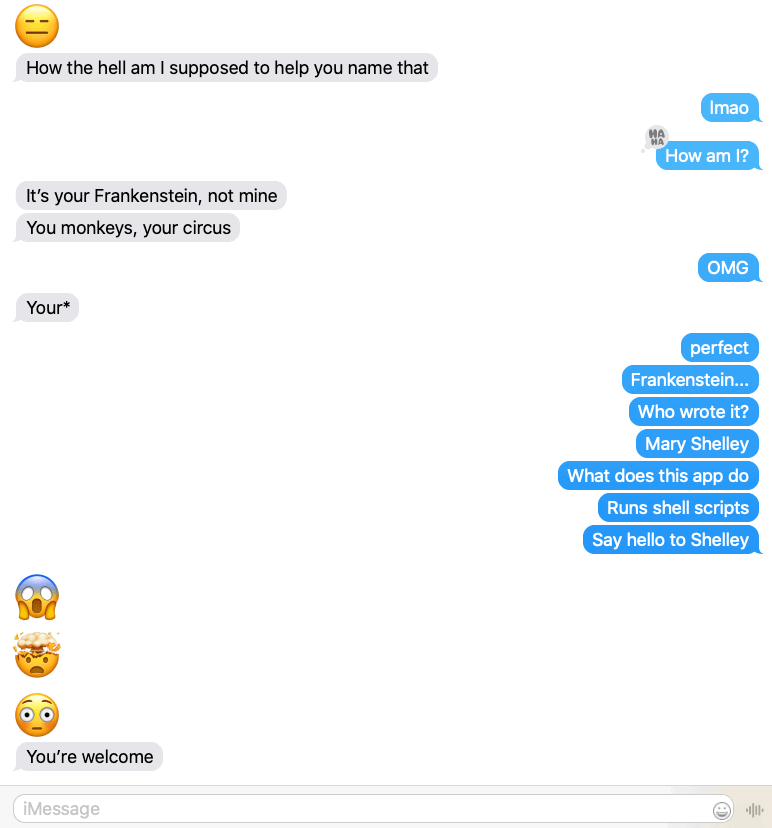

What I came up with is a tiny, macOS menu bar app I call Shelley – because as a friend told me, it’s a Frankenstein of a hack.

Point Shelley at a folder on your Mac containing executable shell scripts. Then, it sits in your menu bar listening for incoming HTTP requests. When an appropriate request arrives along with a secret key, only you know, Shelley looks for a matching shell script and runs it.

The results are instant, and you have the flexibility to script essentially any action on your Mac. Launch apps, open URLs, or even run AppleScripts.

Honestly, I’m not sure what to do with Shelley quite yet. But I remember feeling the same about Hazel, KeyboardMaestro, and even Quicksilver back in the day.

With macOS, the underlying Unix tools combined with a scriptable UI layer means you can automate almost anything.

And like the automation apps above, given enough time and a little imagination, I’m sure I’ll come up with actually useful things to do with Shelley. And I can’t wait to hear what other folks come up with, too.

Here’s how it works…

Shelley Instructions

Shelley runs on port 9876 and listens for a specific HTTP GET request formatted like:

http://some.ip.address/run/<command-name>or

http://some.ip.address/wait/<command-name>To execute one of your scripts, open one of those links in a web browser on another computer, phone, or another device. Or use your favorite scripting tool to send an HTTP request. Or use the iOS Shortcuts.app. Whatever you want.

The example with run will immediately execute your script and return (close the HTTP connection).

If you ping the wait variant instead, the connection will wait and remain open until the script finishes executing.

How does Shelley know which script to run?

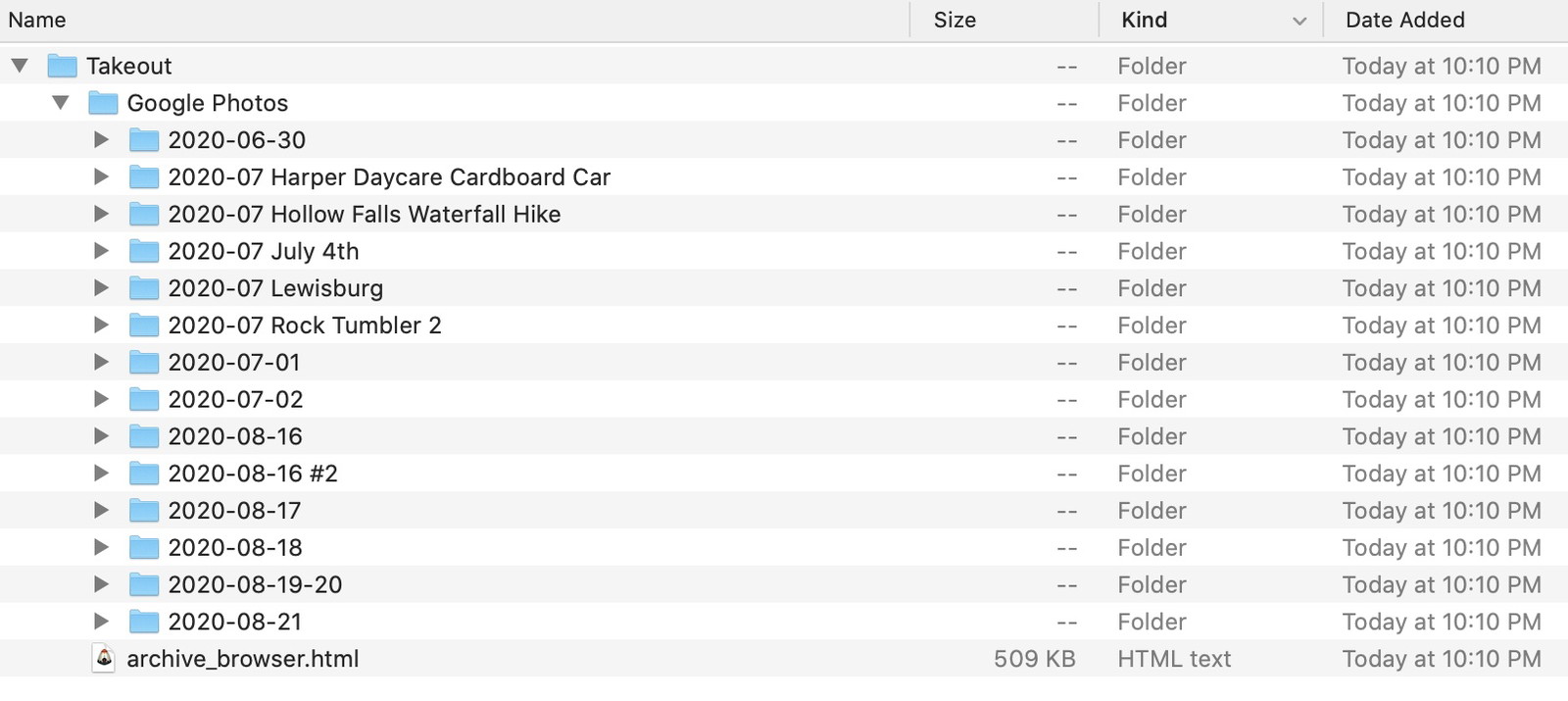

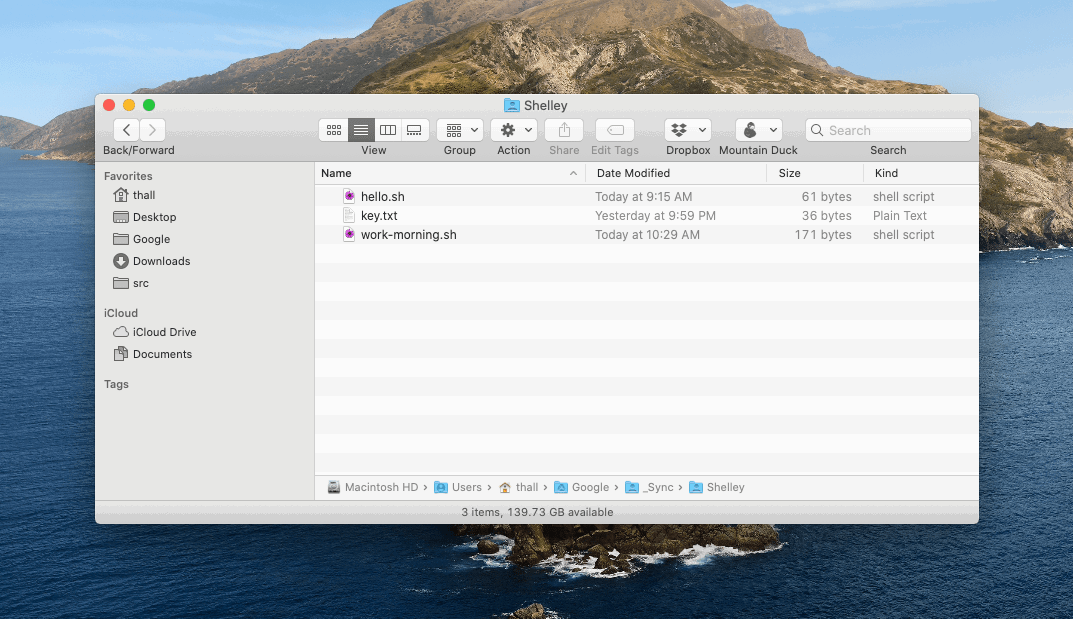

First, open the app’s Preferences and choose a folder to keep your scripts.

Place your shell scripts in this folder. They must be marked executable (chmod +x script.sh) and end with a .sh file extension.

Then, if you wanted to run the work-morning.sh script above, you’d ping your Mac at:

http://some.ip.address/run/work-morningTo keep things somewhat secure, you’ll also need to provide a secret key that only you and Shelley know.

Shelley stores your secret key in the key.txt file automatically added to your scripts folder. (Feel free to modify the random value it picks.)

You can pass that key to Shelley in your HTTP request in one of two ways:

- Through the URL by tacking it on to the end of your GET request:

http://some.ip.address/run/<command-name>/<secret-key>- Or as the value of an HTTP header simply named

key.

That’s all great, but IP addresses change – especially if the Mac you’re targeting is wireless. Luckily, if you’re doing this over a LAN connection, you don’t need your IP address – just your Mac’s Bonjour name.

For my Mac, that would be:

http://tyler-halls-iMac-Pro.local/run/<command-name>That should work on your LAN regardless of if/when your computer’s IP address changes.

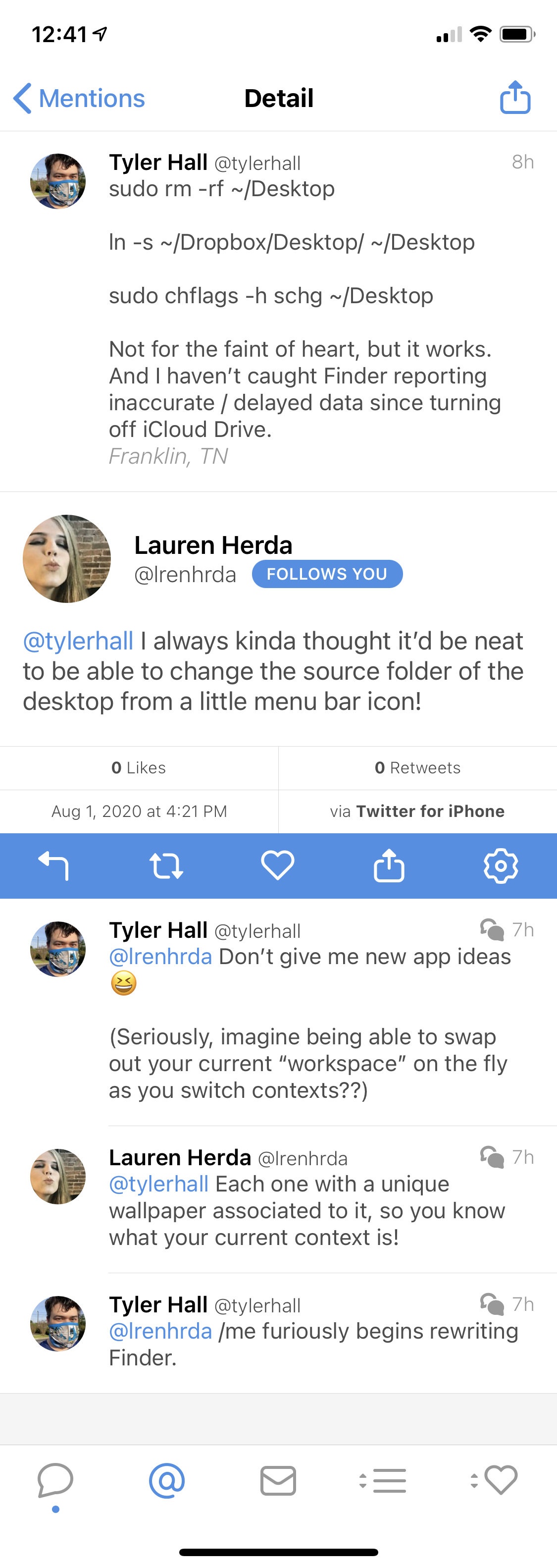

How does all of this tie together with Shortcuts.app and tapping an NFC sticker?

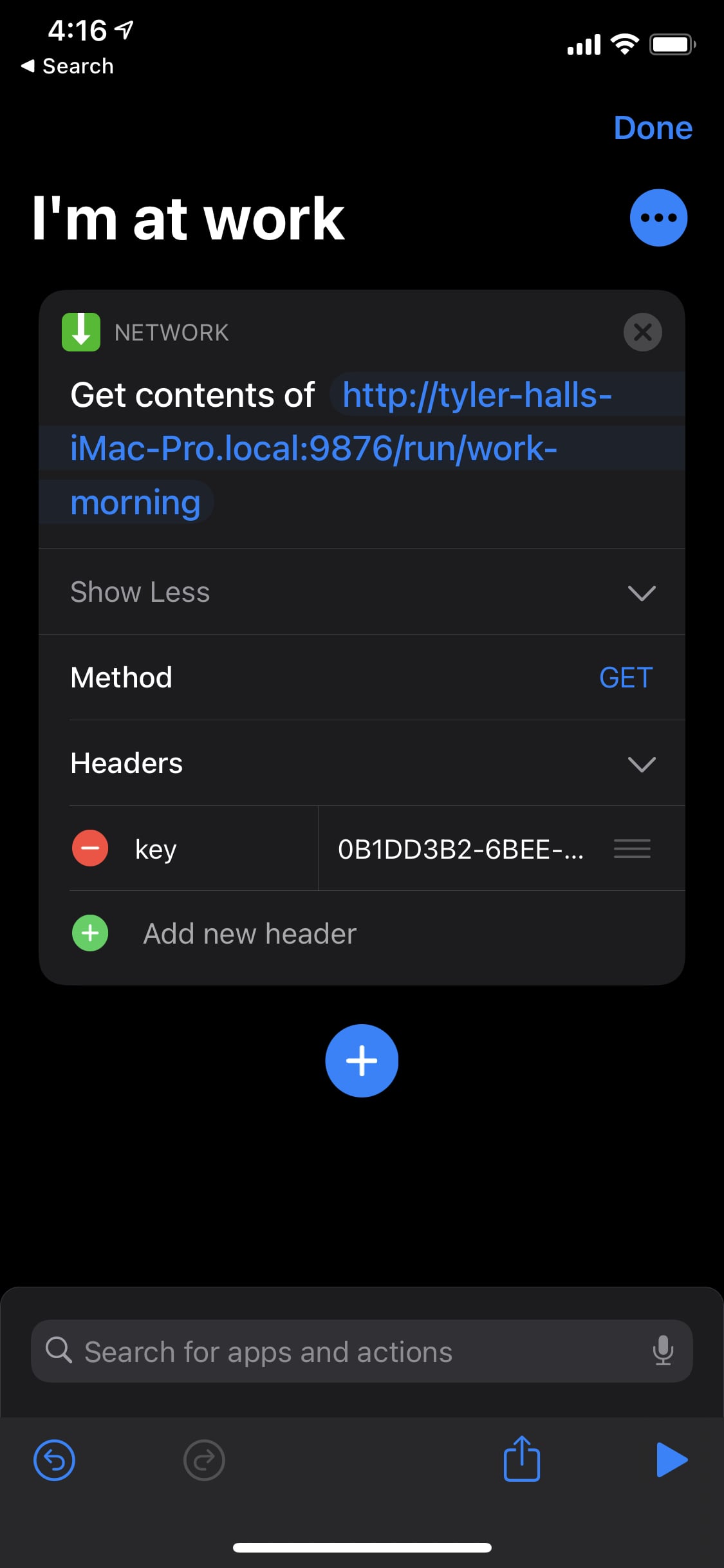

- Create a new Shortcut on your iPhone that looks like:

You’ll notice I’m passing in my secret key using the Headers option provided by the built-in Get contents of URL Shortcut step.

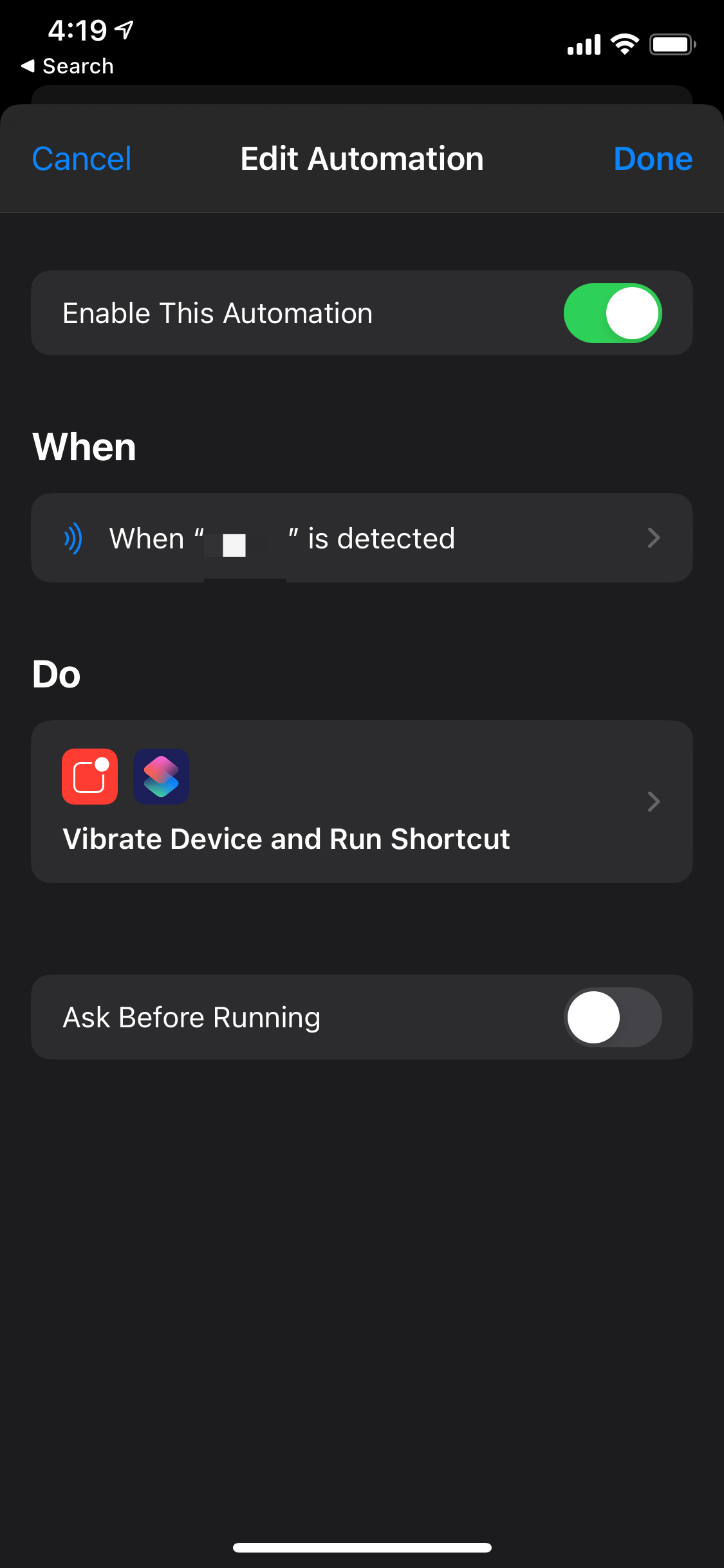

Then, add a new Shortcuts automation to run your shortcut(s) when you tap a specific NFC tag, and boom.

Annnndd, that’s it. From any device that can send an HTTP request to your Mac, you can fire off anything that can be launched by a shell script.

The code is on GitHub and you can download Shelley from here.