This is a joke. But not really. But also, yes. But also sorta serious.

Yesterday, Gruber linked to Jeff Kirvin’s essay “Safari 15 Isn’t Bad, Just Misunderstood”.

I’m not going to weigh in on Safari’s new design. Instead, I want to call out something Gruber wrote in his commentary:

You got URLs in address fields, but page titles weren’t exposed other than in the Window menu. That was, in my opinion, a fundamental flaw in the design. Web page titles are useful, and should be more human-readable than URLs.

That’s something I’ve long intuited based on my own web browsing habits but never really put into words. When I stop and think about it, modern web browsers drive me crazy by limiting tabs to a maximum width because that width is almost never enough to show the full page title.

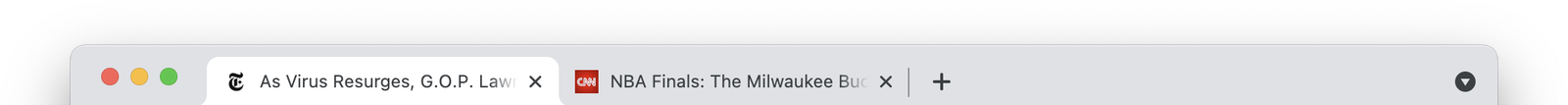

Well, except one web browser: Safari. Look.

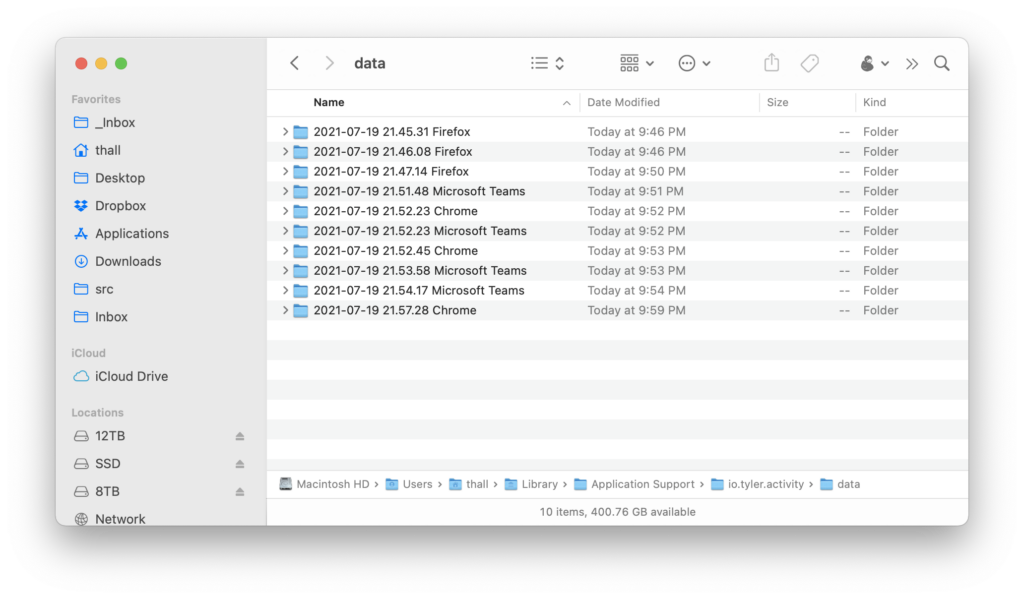

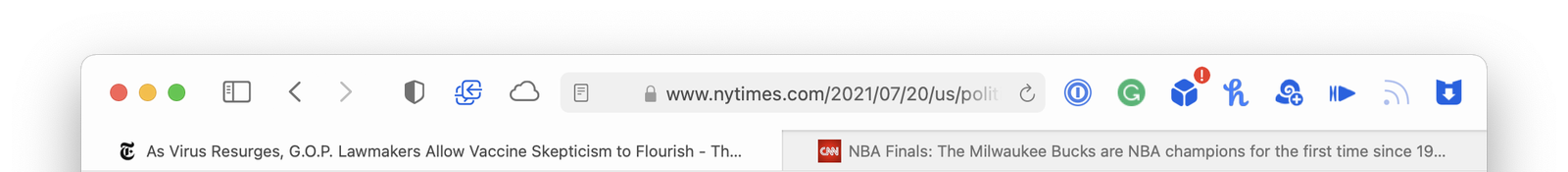

Here’s Chrome, Firefox, and Safari showing the same two web pages using the same window widths.

Chrome

Firefox

Safari

Safari is the only one that lets each tab expand to fill as much room as is available – so you can see more of the web page’s title.

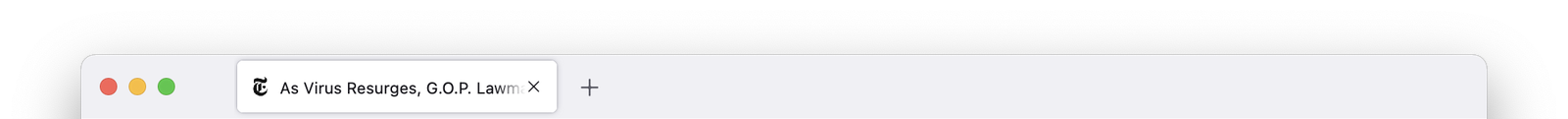

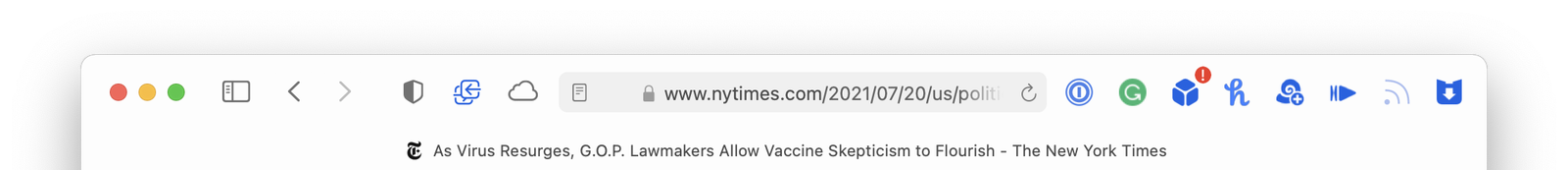

This difference is even more apparent if you only have one tab open. Here they are again:

Chrome

Firefox

Safari

If Safari on macOS Monterey is heading in a similar direction where web page titles are going to be even more truncated, that’s going to make me sad. I guess we should do something about it.

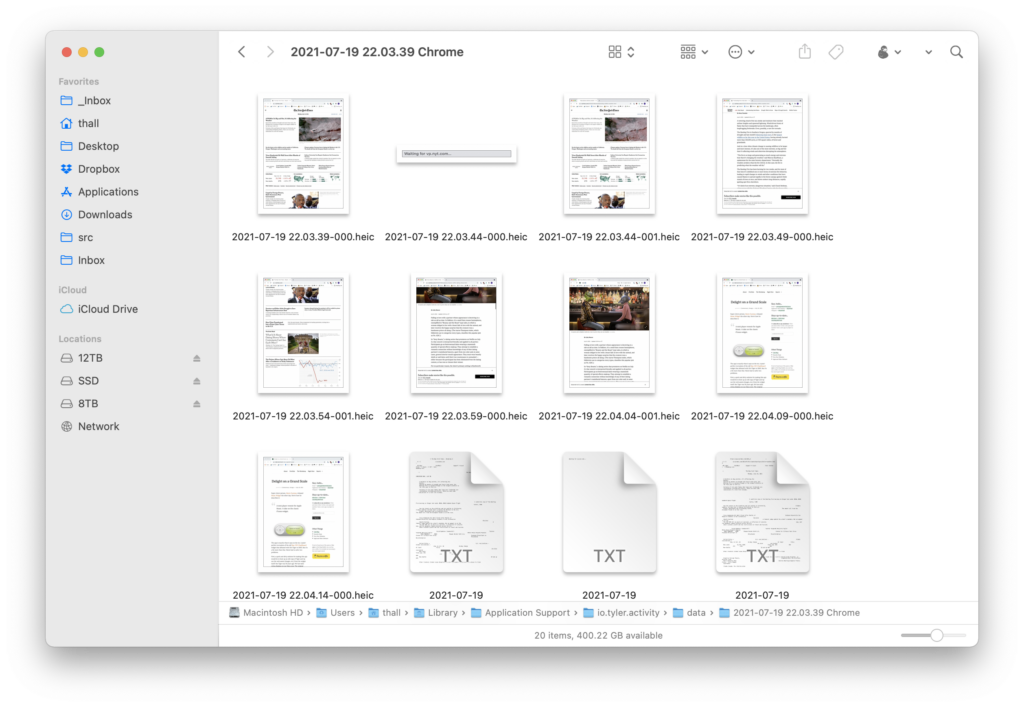

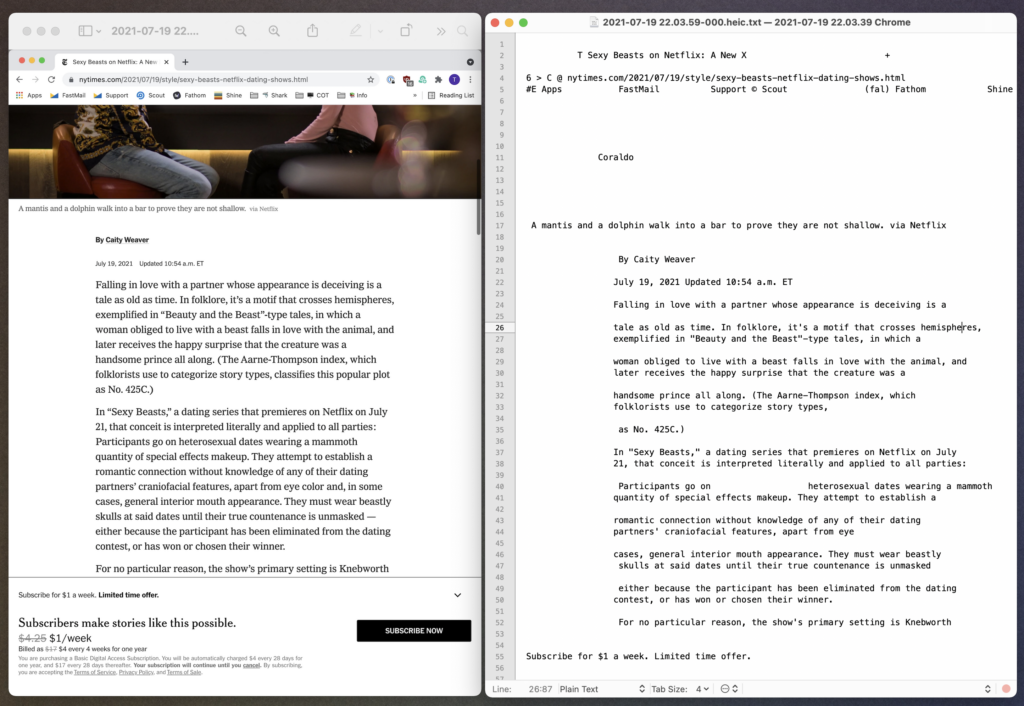

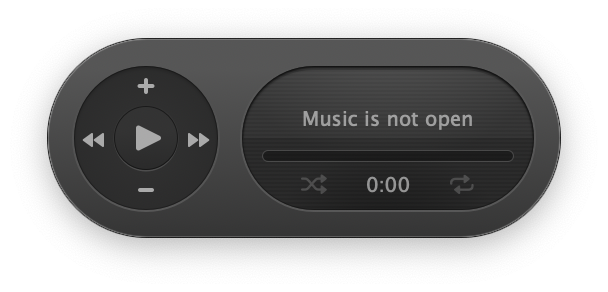

Here’s TheTitle.app

It’s a silly Mac app that is just a window title bar. It floats above all the other windows on your Mac and keeps an eye on your web browsers. As you move from browser to browser and web page to web page, TheTitle shows you the full page title – unobscured. Problem solved.

Here’s a demo video.

And the source is available on GitHub, or you can download a notarized build here.