Stick with me, folks. This is going to get super nerdy and may take a while to explain. It’s also going to cover some of my favorite topics: a custom-built Mac app, a small server-side script, Keyboard Maestro, the command line, and URL schemes.

Let’s talk about the stuff you need to do and the files, supporting documents, and reference material you need to accomplish those tasks. Here’s a quick example:

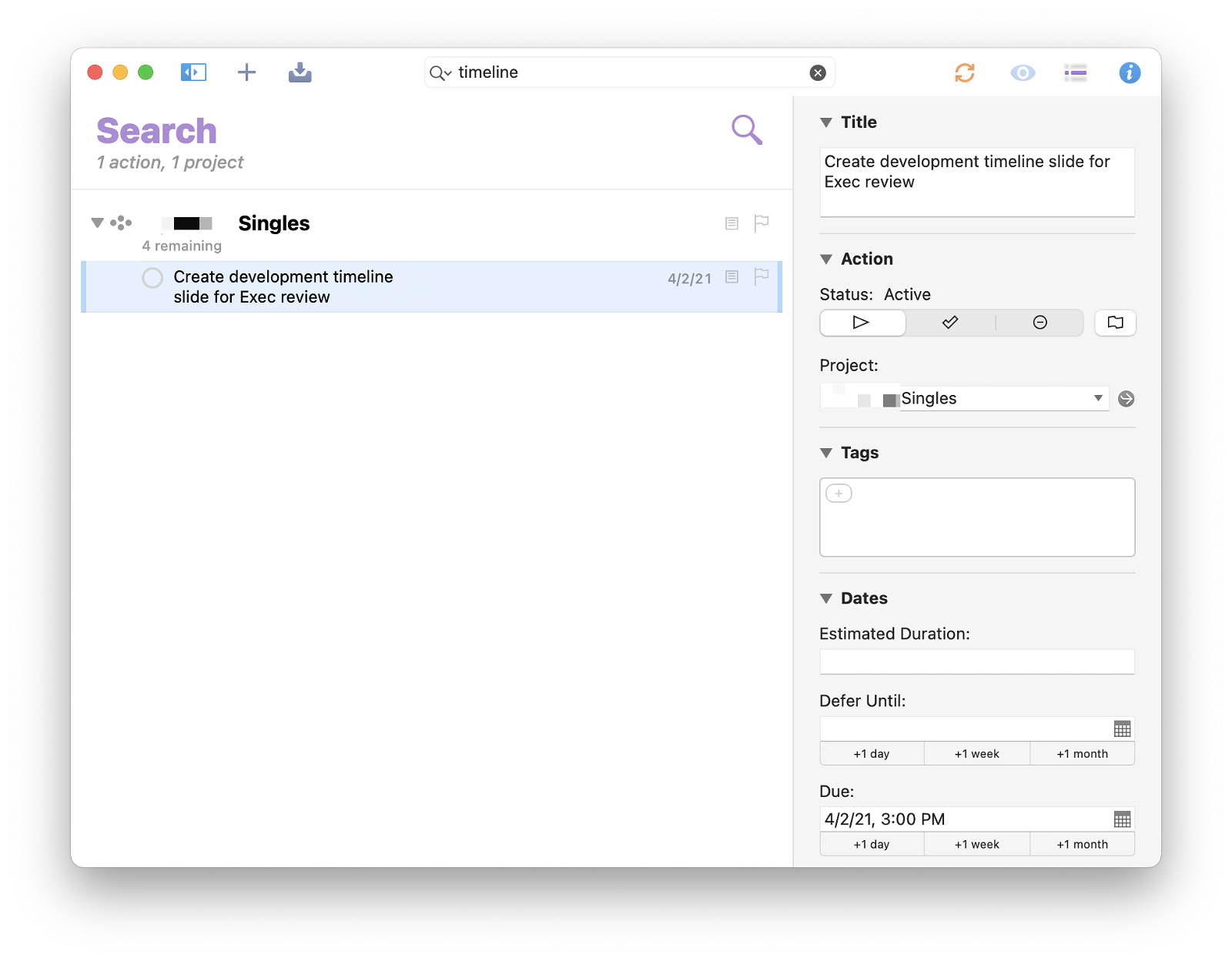

This week I need to prepare a PowerPoint slide outlining our upcoming development timeline and include it in a review deck for the executive team.

Easy, right? But what files do I need to build it?

- an OmniOutliner document that lists our upcoming milestones

- the PowerPoint slide template

- a screenshot of those milestones plotted on a calendar

- a PDF exported from Jira that totals up the development estimates my team added to each ticket

- the OmniGraffle document I’m going to build this in before exporting to PowerPoint

Here’s the problem I’m trying to solve. For my own dumb, neurotic reasons, most of those files live in different places.

- The calendar screenshot is in a dedicated

~/Dropbox/Photos/Screenshots/folder where every screen capture gets saved automatically by CleanShot X. - Because I’m old-school and settled on Omni Sync Server years ago, all of my OmniOutliner and OmniGraffle documents live in

~/Documents/Omni/. - The Jira PDF is on my Desktop because I just now exported it.

- And that PowerPoint template is in a folder full of branding guidelines for work.

That seems typical, right? Everyone has an organizational structure that makes sense to them.

Let’s say I find and gather all those documents to get this slide made. Two weeks go by. Oh, shit. Someone on another team needs the slide for their presentation, but with the information slightly tweaked to reflect schedule changes since I created it.

Where did I put all of those source materials? I can guess where the OmniFiles are. But which screenshot was it? And that PDF was on my Desktop two weeks ago, but where did I end up storing it? Do I even still have it?

That’s the problem I started trying to solve for myself and my workflow last Fall: The issue of keeping track of disparate files that all relate to one another through a common task or goal.

Here’s what the solution looks like from my day-to-day point of view. I’ll explain the mechanics in a bit.

What just happened?

In the notes field of that OmniFocus task, I added this URL: clog://RTH2285. (clog stands for “Catalog”.) And when I clicked on it, it revealed all of my reference files in the Finder.

One immutable URL from any app can open any number of associated files – even if they change locations.

I’ve been using this pattern to tie together related files for the past few months. I’ll catalog files as I create them or receive them (more on that in a moment) and then typically begin my working session on a task by summoning them all forward from a common starting point that contains the magic URL.

Sometimes that starting point is an OmniFocus task, as shown above. Other times it’s a note in Drafts or Ulysses. But it could be any app (or command line, as you’ll see) that can open a URL. It also (to a degree) works on iOS.

I’ll start by explaining this from my (the user’s) perspective and then describe the technical details at the end and link to where you can get the code to do this yourself.

At the heart of this workflow is what I call a catalog number. Each unique number groups a set of related files. Catalog files are in the format [a-zA-Z]{3}[0-9]+. That’s three letters followed only by digits. The first three letters are up to you. They should be uncommon enough not to produce false matches with real words (hold on to that thought).

I chose the prefix RTH (my initials) for my catalog numbers since that combination doesn’t come at the start of any common words. So, example numbers in my system might be:

- RTH2378

- RTH4591

- RTH7730

The numeric portion can be random if you want, but I suggest that it always increments upwards as you assign new numbers. At a high level, that lets me see what order the numbers were assigned – which can occasionally be helpful.

Anyway, once you have a catalog number (again – I’ll explain more of those mechanics soon), you need to assign it to a file. About a month before starting on this system, I wrote another blog post in October titled Dot Dee Tee that explained my habit of adding the current date into my filenames as a sort of embedded reference point.

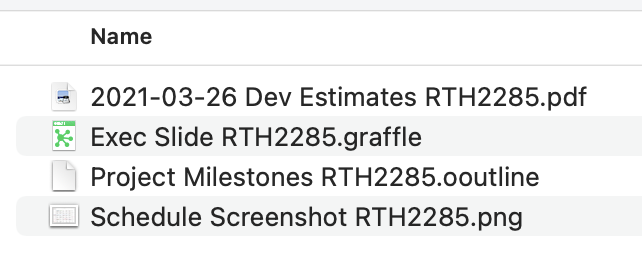

These catalog numbers are similar. The numbers go into the filename. (And file contents, too, as I’ll show.) In my PowerPoint slide task from earlier, my reference files are named:

- Schedule Screenshot RTH2285.png

- Exec Slide RTH2285.graffle

- Project Milestones RTH2285.ooutline

- Schedule Screenshot RTH2285.png

By putting the catalog number into the filenames like a tag (yes, congratulations to me, I invented tagging a mere 29 years after Finder labels, and then OpenMeta, Mavericks, etc.) I can find those files no matter where they move. It also guarantees that the catalog number won’t be lost if synced to a cloud service or zipped up into an archive format that wouldn’t otherwise handle proper filesystem tags.

As I said before, I prefer that my catalog numbers always increment up as I create them. This also makes sure I don’t reuse one if I were generating them at random. But how to keep track of which catalog number comes next? How do I even know what the current one is? Especially if I want this to work cross-device between multiple Macs and iOS devices?

Enter the world’s smallest web service.

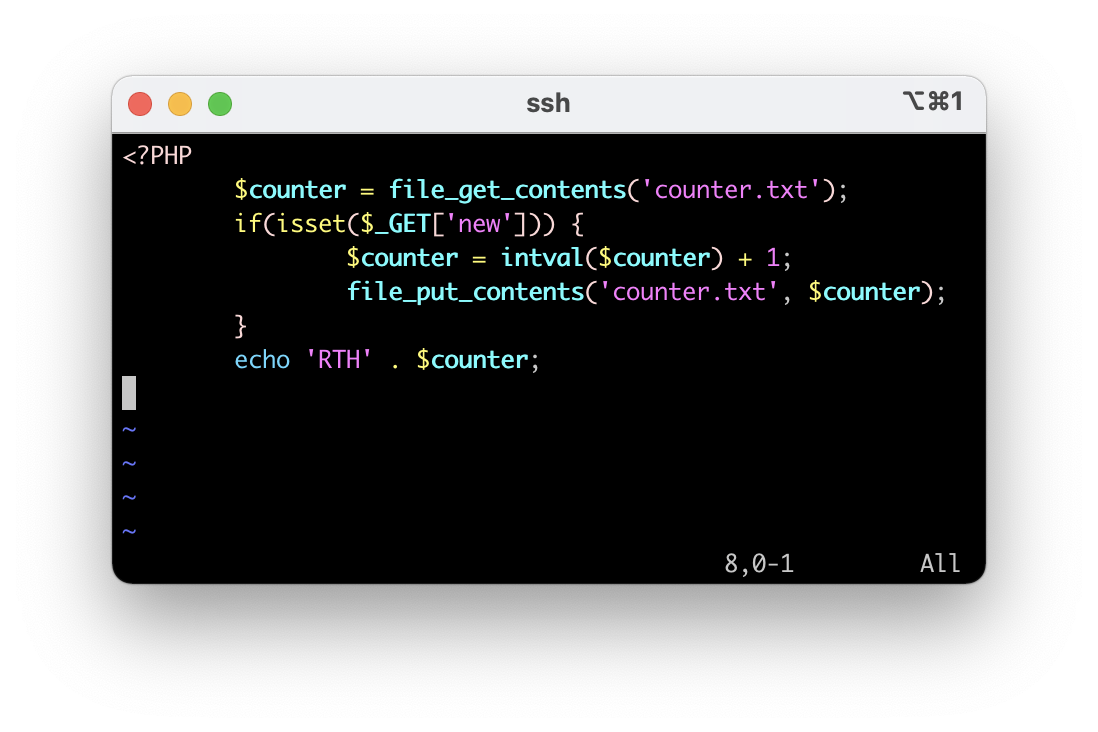

Here’s the entire PHP script I’m hosting on my webserver:

What that does is, if I go to this URL:

https://mywebsite.com/catalog/it prints out the current catalog number contained in the counter.txt file on my server:

RTH1005If I load that URL again, it will show the same number.

But if I load

https://mywebsite.com/catalog/?newit will increment and save the number and print

RTH1006It’s just an extraordinarily simple counter hosted on a web server so I can access it from any device and stay in sync.

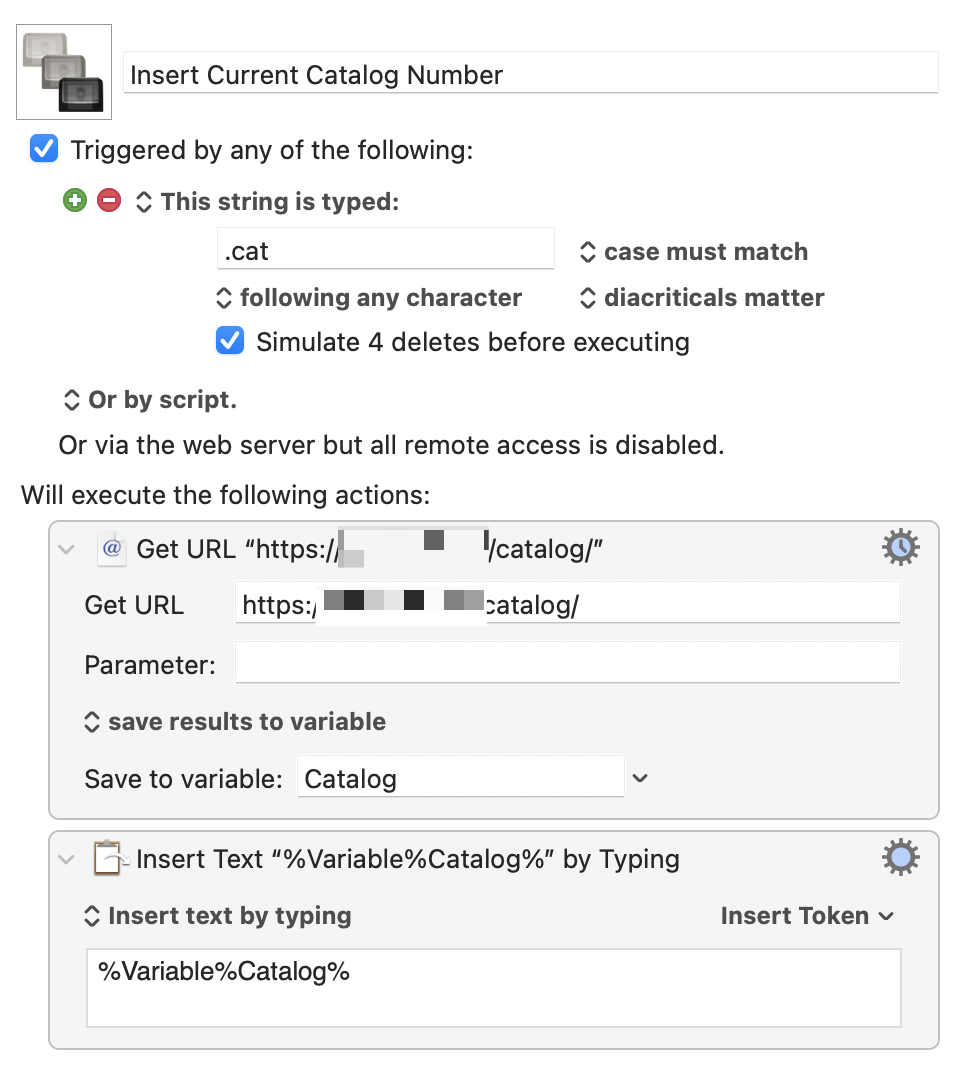

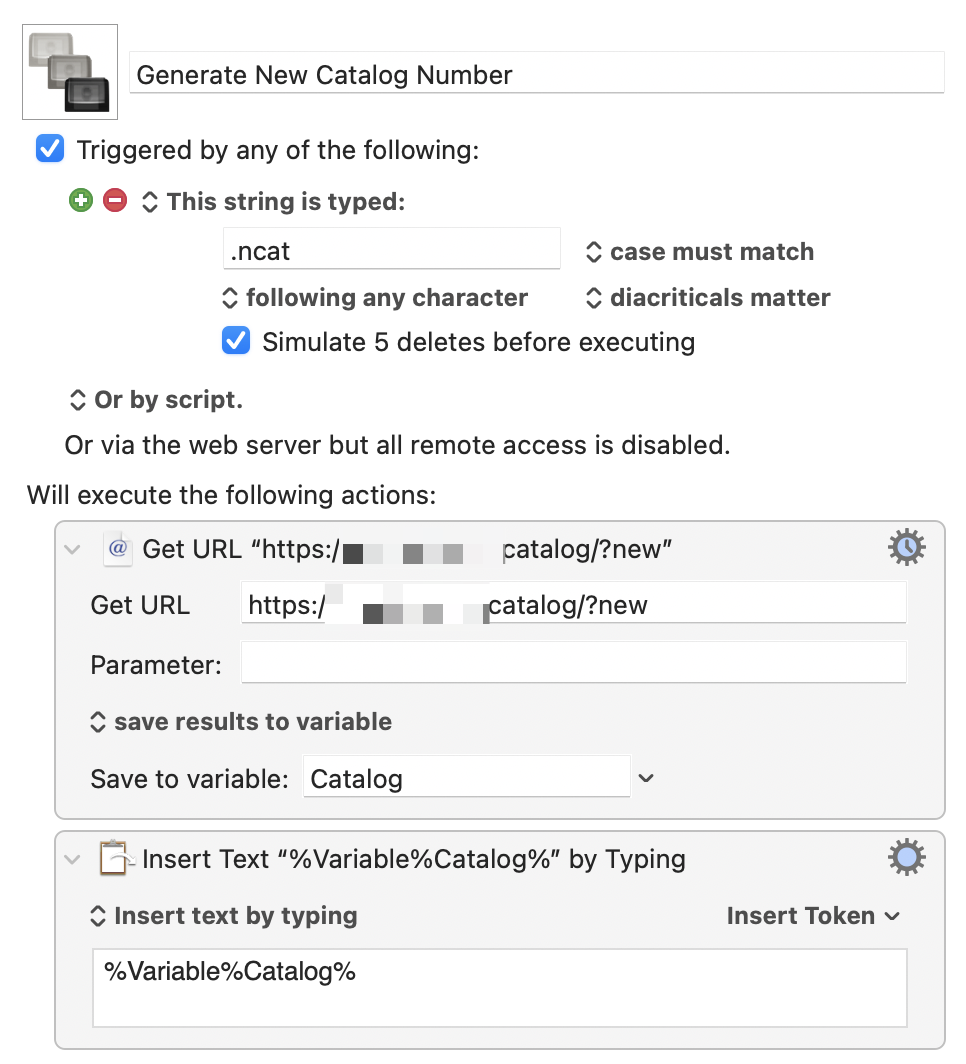

I hear what you’re saying. Having to load a web page just to get a new number every time is cumbersome and slightly insane. I agree. That’s where Keyboard Maestro takes over.

Wherever I am, in a text editor, the Finder, anywhere, if I type

.cat(which stands for catalog) Keyboard Maestro will detect that phrase, make a call to my web service to retrieve the current catalog number, and replace what I just typed with the number.

If I type

.ncat(which stands for new catalog) the same thing happens. Keyboard Maestro increments the number and returns the new one.

Here’s a real example of tagging a file in Finder.

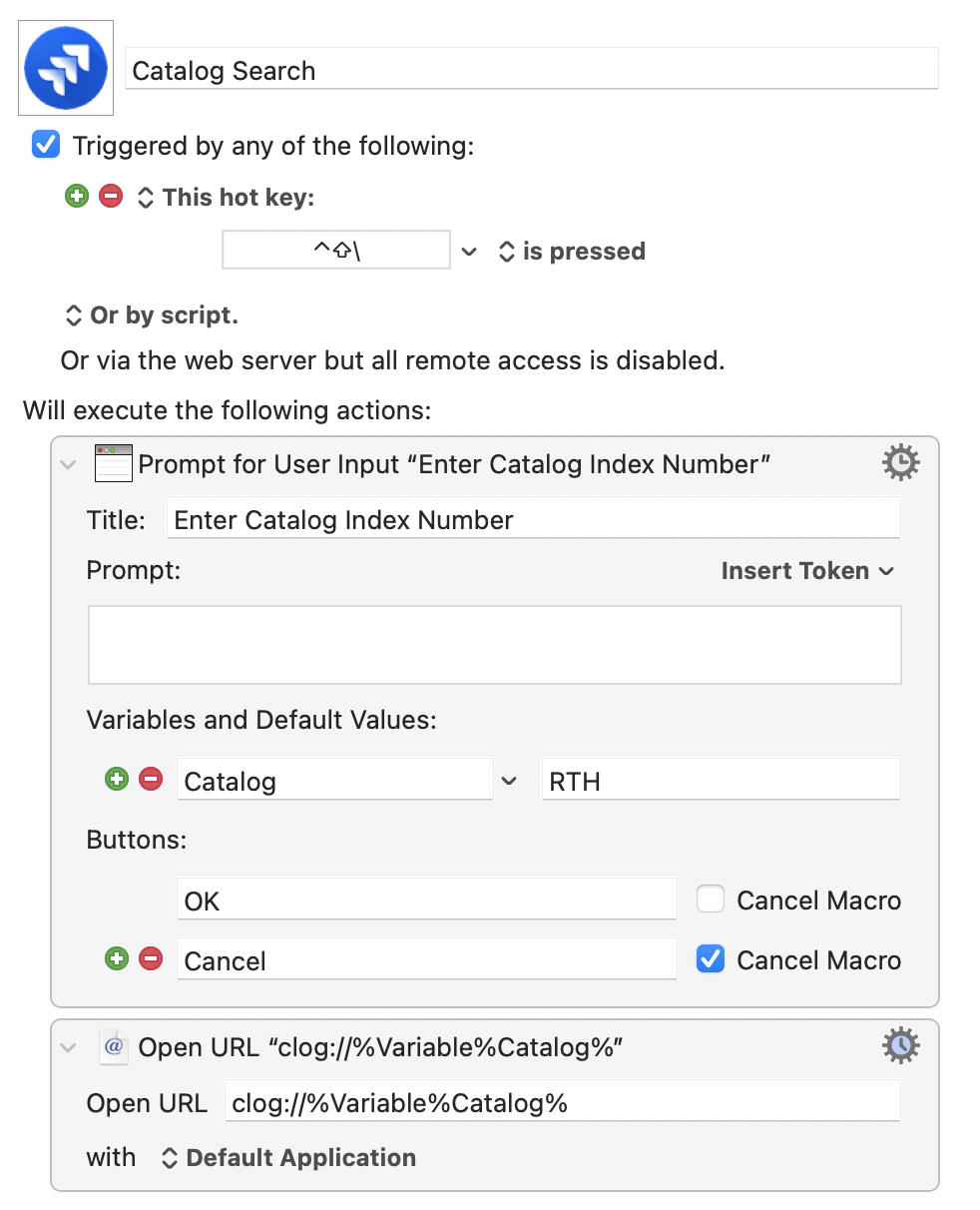

When I want to summon a group of related files, if I’m not in an app where I can click the magic URL, I can again use Keyboard Maestro. This time, instead of tagging a file, it prompts me for the catalog number to create and open the particular URL on the fly and reveal my files.

Ok.

- All of my related files are grouped with a shared catalog number.

- The current and following catalog numbers are kept in-sync using a straightforward web page to track the current and next number to use.

- Just put the catalog number into the filename for safekeeping.

- And a URL in the format of

clog://RTH12345will somehow reveal all of those files for me so I can get to work.

How?

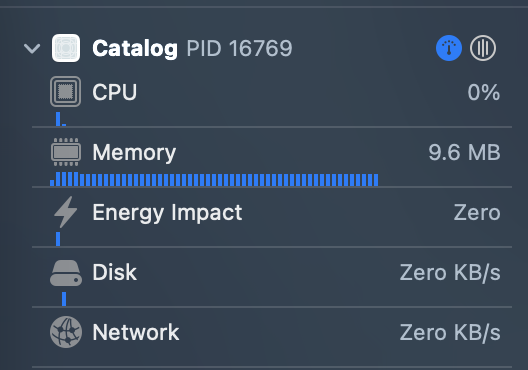

The lynchpin in all of this is a tiny little Mac app that has no UI. It just runs in the background. The whole thing is less than 100 lines of code and takes about 10MB of RAM. (Not GB. Not hundreds of MB. 9.6MB. Like I said, tiny. (By today’s standards.) It doesn’t really do anything.)

It registers the clog:// URL scheme with macOS. And when one of those URLs is opened and matches the correct ABC12345 pattern, it will run a quick Spotlight search for any matching filenames. If found, it reveals each of them in Finder.

That’s it.

There’s also a command-line version. Which lets you reveal files like this

clog RTH2285Or, you can also do

clog --list RTH2285which will output this

/Users/thall/Somewhere/Project Milestones RTH2285.ooutline

/Users/thall/Somewhere/Exec Slide RTH2285.graffle

/Users/thall/Somewhere/Schedule Screenshot RTH2285.png

/Users/thall/Somewhere/2021-03-26 Dev Estimates RTH2285.pdfinstead of revealing the files.

I mentioned two sort-of-bonus-features earlier.

- Full-text search

- iOS support

There’s a hidden option that will find files that have the catalog number inside their contents instead of just a matching filename. For example, if you are in the habit of keeping an archive of plain-text Markdown notes, you can put catalog numbers inside the Markdown files, and the system will find those.

To do this, you need to end the URL with a Z . Why the letter Z? Just because it’s easy to type on a US English keyboard. So, instead of

clog://RTH2285

you would use

clog://RTH2285Z

and that will instruct the Catalog app to have Spotlight look inside your files.

As for iOS, there are two integration points.

- Using catalog numbers in your apps

- Finding matching documents

I’ve set up two Shortcuts and put them in widgets on my home screen. One that grabs the current catalog number and copies it to the clipboard. And the other generates a new one. Then, I can paste them into whatever app or document I’m working with.

Typically, those documents get synced to my Mac. If so, then they’re available there. But I can also search on iOS as well (to an extent).

If you have files in iCloud Drive, you can pull down Spotlight, enter the catalog number, and jump over to the Files app showing your documents.

The same thing works if you keep your files in Dropbox, Google Drive, etc.

So that’s the odd system I’ve been using to jump between tasks and all of their supporting documents. It’s served me well for a while now, along with still using my filename + date strategy, and now I’m open-sourcing the Mac app and PHP script that glue it all together.

I wish I had a better name for the project other than FinderCatalog, but as the old saying goes…