I’ve been a paying customer of Vimeo since 2014 – specifically, their Pro plan.

(Please ignore that the above email receipt is for their Plus plan. Shortly after subscribing I realized I needed to upgrade to Pro, which supports commercial use.)

I needed a reliable way to host a bunch of screencasts and video tutorials I was producing for my software. I went with Vimeo because they’re the obvious choice in this space for two main reasons:

- I didn’t want my content hosted on YouTube where it would be surrounded on all sides by an infinite expanse of flaming garbage. (Don’t take that criticism too harshly – I’m a happy YouTube Premium subscriber.)

- Vimeo is really, really, really good at what they do. I mean, supremely top-notch when it comes to ease-of-use, controlling the end-user experience, speed, and quality.

But when my renewal email arrived in April, myself and other small developers were seeing sales slow down as the pandemic worsened.

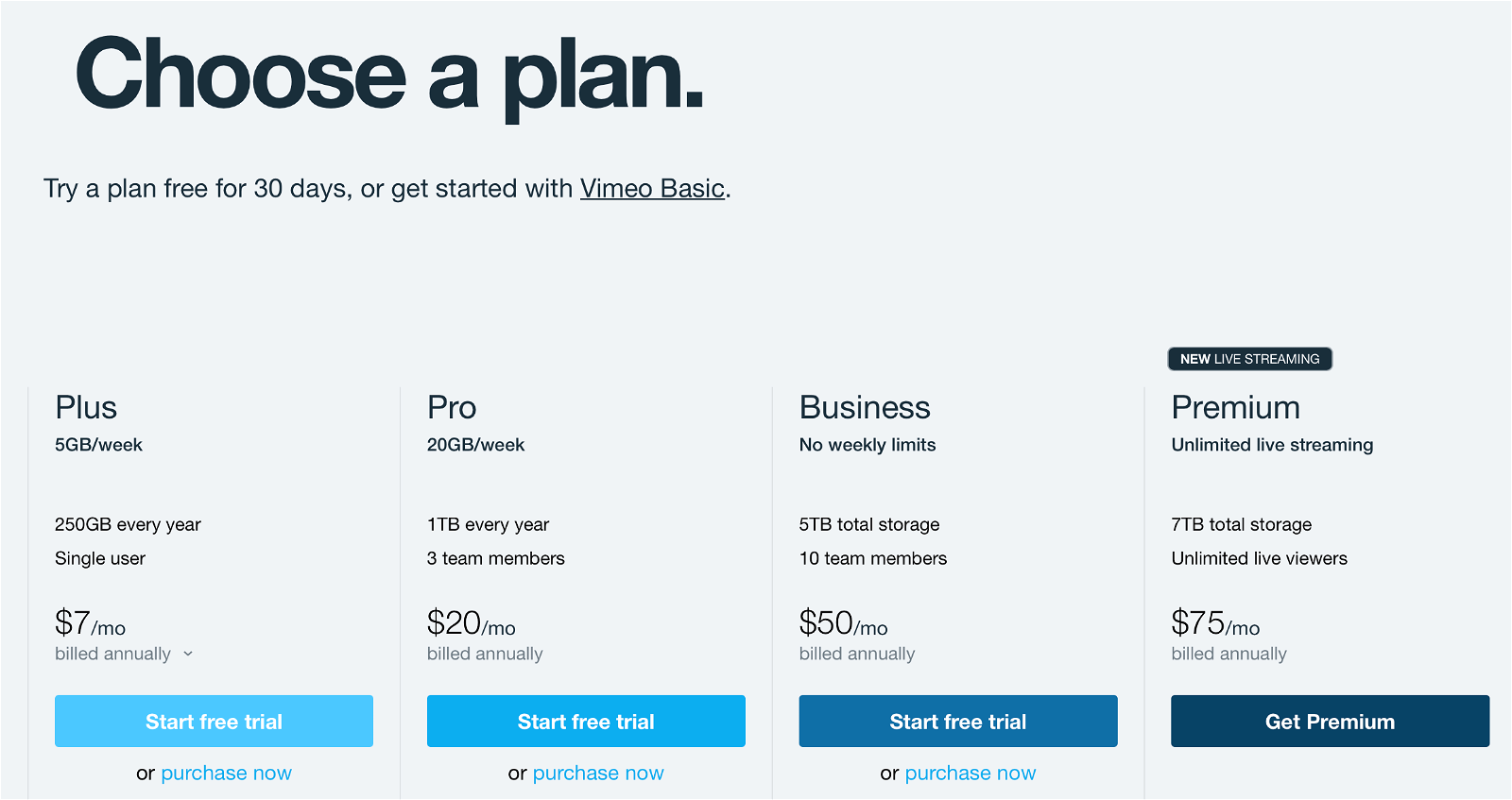

Another $240/year was a tough sell for the small amount of video content I was hosting with them, and I wondered if there might be a cheaper alternative – either another service or by hosting videos myself.

If you’re posting commercial content – like I often do – Vimeo’s terms require you to be a Pro subscriber or higher. And to be clear, I still think Vimeo at that price (at almost any price, really) is a great value. It’s cheaper than a company with four employees paying for Slack.

But at my tiny scale and thinking about cutting costs, given the amount of video content I’m actually posting each month and hosting with them, and also being a huge nerd, it didn’t make sense any longer.

So, let’s do this ourselves.

We need three things:

- Somewhere (cheaper than Vimeo) to serve video from.

- A way to play the video on our website.

- An easy way to convert raw video into an appropriate size and format for streaming.

So, where to actually host the video files? My requirements are somewhere reliable that won’t fall over if you get Slashdotted (ha, remember that?), can deliver quickly to visitors in any location, and won’t bankrupt you.

I have plenty of space available (and almost always enough bandwidth available) on my Linode (affiliate link – but Linode is wonderful) servers. But even my primary $20/month VPS with them was brought to its knees multiple times when traffic spiked. (Granted, I was running WordPress at the time.) And I don’t want to take the chance of my business website going down because one of my dumb blog posts on this website gets noticed.

A lifetime ago, I wrote about using S3 as a poor man’s content delivery network. That’s still an easy and reliable choice, but the cost for bandwidth doesn’t scale as a true CDN. Which is, of course, why Amazon offers CloudFront. But even then, at $0.085/GB, I’ve had multiple months in the past calendar year that would have been over $200.

Instead, let me introduce you to my secret weapon: BunnyCDN. (I get credit if you click that link. But I only use it because I completely love their service as you’ll see below.)

I switched to Bunny last October after using MaxCDN (now StackPath) since 2011 for all of my static assets. And I’ve been utterly flabbergasted at just how damn good they are. For a number of reasons:

- The main metric that matters: they’re really fast. I’m seeing equivalent performance as what I was used to with MaxCDN and the larger CDNs I’ve used at my day job.

- The two times I’ve needed to email them with a support question, a knowledgable, helpful human has replied quickly and without needing to go through dumb self-serve solutions.

- Bunny’s control panel where you manage your account, choose bandwidth settings, etc. is super easy to use and incredibly powerful (at least for my needs). It’s a really nice change from what I had with MaxCDN and the AWS Console (powerful as hell, but obtuse).

- Holeeeee crap their bandwidth is cheap.

For my static website assets (images, stylesheets, JavaScript, etc.) I use Bunny’s standard tier, which serves my content from all of their PoPs. That means visitors will connect to the server closest to them at $0.01/GB (for US and EU PoPs).

However, my video content uses their volume tier, which is distributed from 7 PoPs (instead of 41). While still being plenty fast enough, that reduces the cost further to $0.005/GB. That works out to a cool $5/TB when my traffic spikes.

I have zero understanding of how bandwidth is actually priced globally between providers or why some companies charge such a premium compared to others for the same bits over the wire. I assume you’re paying for reliability and/or speed? All I know is that I haven’t seen a blip of downtime or noticed any slowness in the nine months I’ve used BunnyCDN. I can’t explain how they can be so much less expensive. Maybe they won’t scale to “real” traffic? But for what I need, they’ve been a phenomenal choice.

(Ok, I’m done going on and on about them now. This really isn’t any sort of paid or sponsored content crap for Bunny. I’ve just been so impressed since switching, that I finally wanted to give them recognition.)

So that’s my answer to point #1 – where to host the video files.

The next thing we need is a way to show those videos inline on your website.

Gone are the days of embedded Flash video. Now, you can mostly get away with just using the native HTML5 video element.

However, if you want more control over the appearance of your video and how it behaves, take a look at Video.js. It’s a wonderful open source player from the kind folks at Brightcove that provides a similar level of control as the point and click customization options that Vimeo offers.

The last puzzle piece is getting your original videos into a web-friendly format and uploading them for distribution.

BunnyCDN offers their own online storage zones that you can simply upload to via FTP, but for historical reasons, I still store my large app downloads and videos on S3 and then have Bunny (and previously MaxCDN) pull from AWS as an origin server.

And as for the correct video format, I’m using Handbrake’s command line interface to convert my source videos files into mp4 using the Vimeo YouTube HQ 720p60 and Vimeo YouTube HQ 1080p60 presets.

But, because, hey, I’m a geek who doesn’t like doing extra work, I’ve wrapped up the whole process into a short shell script that

- Converts the source video to 720p

- Converts the source video to 1080p

- Uses

qlmanageto output a frame of the video as apngfor previewing in the HTML player before the video starts imagemagickto convert thatpngto ajpg- Uploads all three assets to S3 with

s3cmd - Outputs the custom shortcode I use to embed videos in my blog posts

I just pass my video’s filename to that script, and a few minutes later I can copy and paste the output into my text editor and make it available on my website. Honestly, it’s an even faster process than using Vimeo.

Here’s the script. You’ll of course want to modify the paths to make it work with your own setup since it’s completely specific to my needs right now.

#!/bin/bash

bucket=$1

base=$(basename -- "$2")

extension="${base##*.}"

filename="${base%.*}"

p720="/Users/thall/Dropbox/Freelance/Videos/720p/$filename.mp4"

p1080="/Users/thall/Dropbox/Freelance/Videos/1080p/$filename.mp4"

png="/Users/thall/Dropbox/Freelance/Videos/jpg/$base.png"

jpg="/Users/thall/Dropbox/Freelance/Videos/jpg/$filename.jpg"

/usr/local/bin/HandBrakeCLI -Z "Vimeo YouTube HQ 720p60" -i "$2" -o $p720

/usr/local/bin/HandBrakeCLI -Z "Vimeo YouTube HQ 1080p60" -i "$2" -o $p1080

/usr/bin/qlmanage -t "$2" -s 1080 -o "/Users/thall/Dropbox/Freelance/Videos/jpg/"

/usr/local/bin/magick convert $png $jpg

rm $png

s3cmd put --acl-public --guess-mime-type $p720 "s3://$bucket/720p/$base"

s3cmd put --acl-public --guess-mime-type $p1080 "s3://$bucket/1080p/$base"

s3cmd put --acl-public --guess-mime-type $jpg "s3://$bucket/jpg/$filename.jpg"

echo "[tylervideo url=\"$base\" img=\"$filename.jpg\"]"So that’s how I moved off Vimeo and started hosting my video content myself. On average, my bandwidth bill is about $11/month – and that includes videos, static assets, and ALSO binary downloads for all of my Mac apps. Previously, I was paying $20/month just for video hosting on top of the rest of my bandwidth.

It’s definitely a geekier solution that requires more work up front to setup, and I’m not sure I would recommend it for a “real” business, but for my needs it was a fun project and I’m happy to save $200 a year.