This is a blog post in two parts.

The first is about something I built for my son that brought me, well, joy. And the second half is the realization I later came to that made me very sad.

I’m Not a Carpenter

I recently found out that my father-in-law doesn’t (and hasn’t ever) respected me as a “real man” because I don’t work with my hands for a living. I don’t spend my weekends in the garage fixing cars or in the backyard building a deck.

Given the right YouTube video, I’m capable of doing basic repairs and solving problems myself, but that type of work isn’t a skill I grew up learning.

But to think I don’t “build things” is disingenuous and highlights a real generation gap in understanding what “work” used to be (and still is) and what it can be (and is) for more and more people.

I say all of that first to vent and get it off my chest. But second, to illustrate that the iPad app I built last night and this morning is a real thing that (hopefully) solves a real problem just as much as repairing the guest toilet or changing my own oil would.

My son is in first grade and loves stories, but he’s having trouble reading. It’s not that he doesn’t know his sight words or can’t sound out letters. It’s that he’s just like me and inherited one of my worst traits. We both hate doing things we’re not immediately good at.

For him, that means that as soon as he comes to a new word, he gets frustrated and shuts down if he has any trouble figuring it out.

So I’ve been looking for a way to encourage him to keep trying and stay engaged.

Luckily, he’s six. And six-year-old boys are pretty easy to figure out. For him, that means anything involving Super Mario or Black Panther is bound to pique his interest.

I had the idea for this app right after the kids fell asleep last night, and I stayed up late to make it.

My idea was to gamify his reading sessions. I know there are tons of apps out there to help kids read, but building software is what I do for a living. I wanted to use those skills that my father-in-law looks down on and make something special and unique just for my son. Maybe one day I’ll build him a treehouse. But last night, I built him this app.

And, naturally, the source is available on GitHub if you’d like to play along at home.

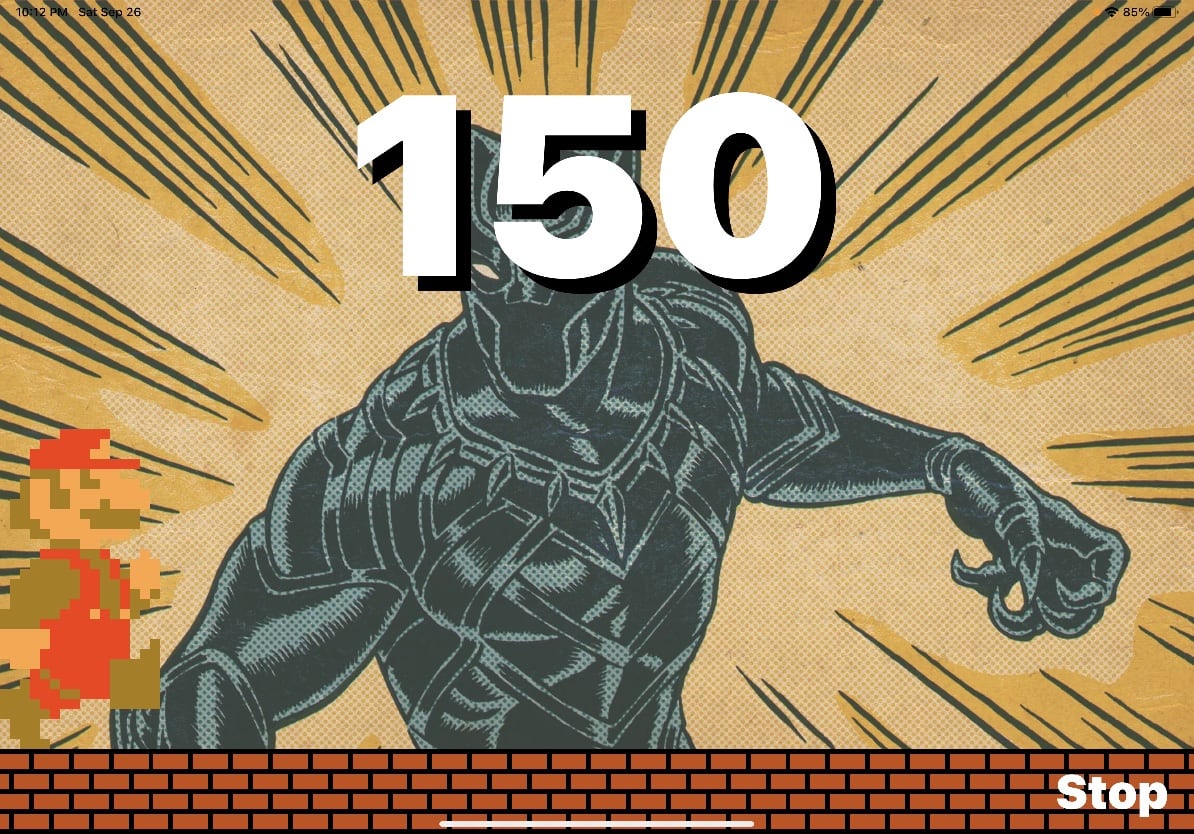

It’s a simple, one-screen iPad app. The goal is to move Mario across the iPad.

How do you do that? By reading a book.

When a new game starts, the app listens for my son to read a book out loud, and iOS does on-device speech-to-text. With every word he reads, Mario runs further and further across the screen. A live counter ticks down from his word count goal. And when the counter reaches zero and Mario reaches the other side of the iPad, my son gets rewarded with confetti, Mario jumping up and down, and the official Super Mario end-of-world theme music.

What does my son think of his new app? Judge for yourself…

Besides sprinting across the screen, Mario does have another trick up his sleeve. To keep things interesting, at any point when he’s reading, if my son shouts, “Jump!,” Mario will dutifully jump on screen.

Will this app solve my kid’s reading problems? Probably not. Even though my wife is already talking to me about adding additional in-app rewards and bonuses to keep him motivated, I’m sure he’ll be bored with it within a week.

And that’s ok. My larger reason for building the app brings me to the second half of this post.

Modern Software is Designed Not to Last

If you’ve followed this blog for any length of time, you’ll find that I take preserving our (my family’s) digital memories and history seriously. I think it comes from watching my mom put together countless family photo albums and my dad doing decades of genealogy research.

And I’ve applied my digital hoarding habits to our photos, videos, old videotapes from the 80s, scanned physical documents, and even interviewed and recorded grandparents before they passed.

At the start of the pandemic, I began recording myself reading poems by Shel Silverstein every night. He’s my kids’ favorite author / poet. My goal is to read aloud every poem he published and put those audio recordings in some sort of digital archive for my kids. And while I certainly hope I’m not dead anytime soon, I wanted to create a keepsake from me to them that they can look back on when they’re older.

The realization I had last night while building my son’s app, is that as long as I put those poetry recordings somewhere safe and practical, they should last a generation or more. I’m not overly worried about mp3 files (or wav or whatever) bit-rotting and becoming unplayable. Our family photo archives are probably safe as jpg files. (I’m talking file formats, not necessarily the storage medium, which is an entirely different rabbit hole.)

As a society, we spend so much time preserving and protecting artifacts and artistic works from hundreds and even thousands of years ago. It’s just how we’re wired.

I made a joke on Twitter that my legacy and contribution to this world will be the hundreds of abandoned git repos my family finds on my computer when I die. (Or maybe even farther in the future than that.)

And there’s real truth to that.

I’m not a musician or an artist or a novelist. If I recorded music, made paintings, or penned a seven-volume teen vampire young-adult book series, those things would outlast me.

But this app I made for my son? I built it because I thought it might help, sure, and because software is what I do. It’s my life’s output, my legacy, and I wanted him to have his own piece that belongs only to him.

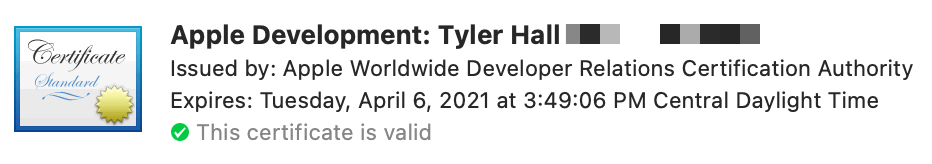

Unfortunately, I write software for Apple’s platforms. And on iOS (and increasingly on macOS), that requires code signing and Apple’s blessing to do anything.

And so if I were to die tomorrow, the app I made just for him and installed on his iPad this morning will stop working in one-hundred and ninety-two days. Not for any technical reason. Not because of future software incompatibilities. If his iPad remained in working order for another hundred years, it wouldn’t even matter. This digital heirloom will self-destruct as soon as my developer certificate expires.

And it’s all due to an arbitrary decision on Apple’s part to lock down their platform(s) to maintain control and protect profits.

And so with all the recent anti-trust rumblings, this is the part that worries me the most.

Sure, it’d be great if Apple’s App Store commission (tax) aligned with the value they provide developers. And I bitch all the time online about the capriciousness and borderline hostility of App Review.

But those are relatively minor concerns in the grand scheme of things. My ask is that Apple’s customers (and this applies to all platforms across the industry) regain the right to run the software of their choosing.

I patently reject the notion that you can enjoy the marketing benefits of claiming your platform is a replacement for a computer when your customers can’t run their own software on it.

Cupertino could allay anti-trust concerns, and I’m serious when I say this, provide an amazing gift to the world and future generations if they’d stop being the worst version of themselves and allow side-loading. And they could do this while continuing to do swan dives into literally infinite Scrooge McDuck sized vaults of cash.

Our world is digital now. And that means our heritage is, too.

I don’t think I’m being hyperbolic when I say that future historians and even archaeologists are going to revisit our time and be furious at the direction our industry turned towards using consolidation, monopoly power, and artificial restrictions to protect profits at all costs.

Imagine if Howard Carter discovered King Tut’s tomb but couldn’t open the door because the Pharaoh’s signing certificate had expired.